Introduction

In a prior blog, the role of the supplemental diagnoses file was discussed in relation to risk adjustment for the Affordable Care Act Risk Adjustment (ACA RA) program. More specifically, diagnoses on the supplemental file were shown to increase risk scores by approximately 10% on average. This is important since health plan risk scores are the basis for RA transfer payments that plans either make to or receive from other plans. Given the importance of the supplemental diagnoses, we will also take a deeper dive on it in this blog, where we explore the distribution of supplemental diagnoses by the level of their failure rate. We start by providing some background on how failure rates are calculated and how they factor into the risk adjustment data validation (RADV) process, which culminates in annual RA transfer payments.

Why are failure rates important for RADV?

Failure rates are a key component of the RADV process. Failure rates provide a measure of the accuracy of hierarchical condition category (HCC) coding for a plan relative to other market participants. Importantly, the failure rate is not a direct reflection of the accuracy of a single plan’s HCC coding. Instead, it aims to gauge whether the coding practices of the plan are outside of nationwide norms for all plans. Plans found to have significant differences in coding relative to the nationwide norm are identified as “outliers” and receive risk score adjustments to correct the relative over- or under-identification of HCCs.

How are failure rates calculated?

The failure rate refers to the errors found during the RADV audits when comparing diagnoses submitted by plans in the Enrollee-Level External Data Gathering Environment (EDGE), including the supplemental diagnoses file, with the diagnoses that are supported in medical records. A failure rate is calculated for each HCC. The formula is essentially one minus the ratio of the validated HCC count from the medical record review to the HCC count in EDGE. A positive failure rate means there were more HCCs submitted to EDGE than could be validated by medical record documentation submitted for review. A negative failure rate means there were more HCCs validated by medical records submitted for review than were submitted to EDGE. HCC failures may be the result of invalid documentation, missing or insufficient medical record documentation, or incorrect/missing diagnosis coding. Failure rates at the plan level are calculated based on a sample of enrollees used for RADV.

What are failure rate groups?

At the plan level, the sample size of each unique HCC would be too small to provide enough data for statistical analysis, especially for rare conditions. To increase the sample size, all HCCs are grouped into one of three HCC failure rate groups — “Low,” “Medium,” and “High” — based upon the value of their national failure rates. The failure rate groups are also created such that each group has approximately equal frequencies based upon what is in the EDGE data for all plans.

More specifically, first, failure rates are calculated for each HCC (in the case where HCCs are part of a super HCC, the failure rate is calculated at the super HCC level). Then the HCCs are ordered by their failure rates, lowest to highest. The HCC with the lowest failure rate is assigned to the Low failure rate group. Then the next lowest HCCs are assigned to the Low group, until the cumulative size of the group reaches approximately one-third of the total frequency of HCCs in the EDGE data. At that point, the next HCC is assigned to the Medium group. Additional HCCs are added to the Medium group until the cumulative size of the Low and Medium groups reaches approximately two-thirds of the total frequency of HCCs in the EDGE data. The remaining HCCs are assigned to the High failure rate group. After all of the HCCs have been initially assigned, some tweaks may be made to help ensure that each failure rate group comprises near one-third of the total frequency of HCCs in the EDGE data.

At the conclusion of the process, each HCC is assigned to only one of the three failure rate groups. The categorization process aims to allocate HCCs so that each HCC Failure Rate Group has a relatively equal proportion of the total frequency of HCCs when summed across all plans. Because there is significant variation in the incidence of HCCs, the count of unique HCCs will not necessarily be evenly distributed across groups. For example, for the 2018 benefit year RADV, there were 33 HCCs grouped in the Low failure rate group, 32 in the Medium group, and 63 in the High group. The High group tended to be associated with HCCs that have smaller frequencies in the EDGE data.

Why are failure rate groups used?

As mentioned above, many plans would have too small of a sample size to support meaningful failure rate statistics at the HCC-level. However, comparing plan-level to national-level failure rates across all HCCs would likely create biases for plans that have a substantially different mix of HCCs relative to the national distribution. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the federal agency responsible for the ACA RA process, believes that grouping the HCCs results in a more equitable process for determining which plans are outliers, while ensuring enough sample size for statistical analysis of outliers (discussed in more detailed below).

How are outliers identified?

The determination of outliers for each HCC failure rate group is based on the difference in a health plan’s group failure rate compared to the national average group failure rate. More specifically, any health plan with a group failure rate outside of the 90% confidence interval (or 1.645 standard deviations from the mean) in any HCC failure rate group will be considered an outlier (prior to the 2019 benefit year RADV, a 95% confidence interval was used). The confidence interval estimates the range within which the average plan group failure rate should lie 90% of the time. CMS believes that some variation and error should be expected; hence, this approach aims to limit adjustments for cases when a group of HCCs are found to have a statistically significant difference from the nationwide mean failure rate. Also beginning with the 2019 benefit year, a plan is not considered an outlier for an HCC failure rate group in which it has fewer than 30 EDGE HCCs (again helping to ensure sufficient sample size for statistical analyses).

How is the adjustment calculated and applied?

Any health plan identified as an outlier for any of the failure rate groups will have their risk scores adjusted. Full details on the process are provided in the CMS RADV protocols. In general, the first step is to calculate a risk score for each of the plan’s enrollees using the data in EDGE. Then the risk score for each enrollee is adjusted if the enrollee has an HCC in an outlier HCC group. The adjustment is only applied to the HCC(s) in the outlier group and equals the difference between the plan’s HCC group failure rate and the national HCC group failure rate. In essence, enrollees with outlier HCCs have a new risk score calculated as if the plan’s coding was more like the national average.

After the EDGE risk scores and Adjusted EDGE risk scores have been calculated for each enrollee, the average of the difference between the two scores is calculated, controlling for the distribution of different types of enrollees that were sampled as part of RADV (i.e., RADV generally uses 10 strata for sampling including subgroups for adults and children). Finally, a plan-level “error rate” is calculated as one minus the ratio of the average adjusted EDGE risk score over the average EDGE risk score. This error rate is applied to the plan-level risk score in the transfer payment calculation.

Failure rate group HCCs and supplemental diagnosis codes

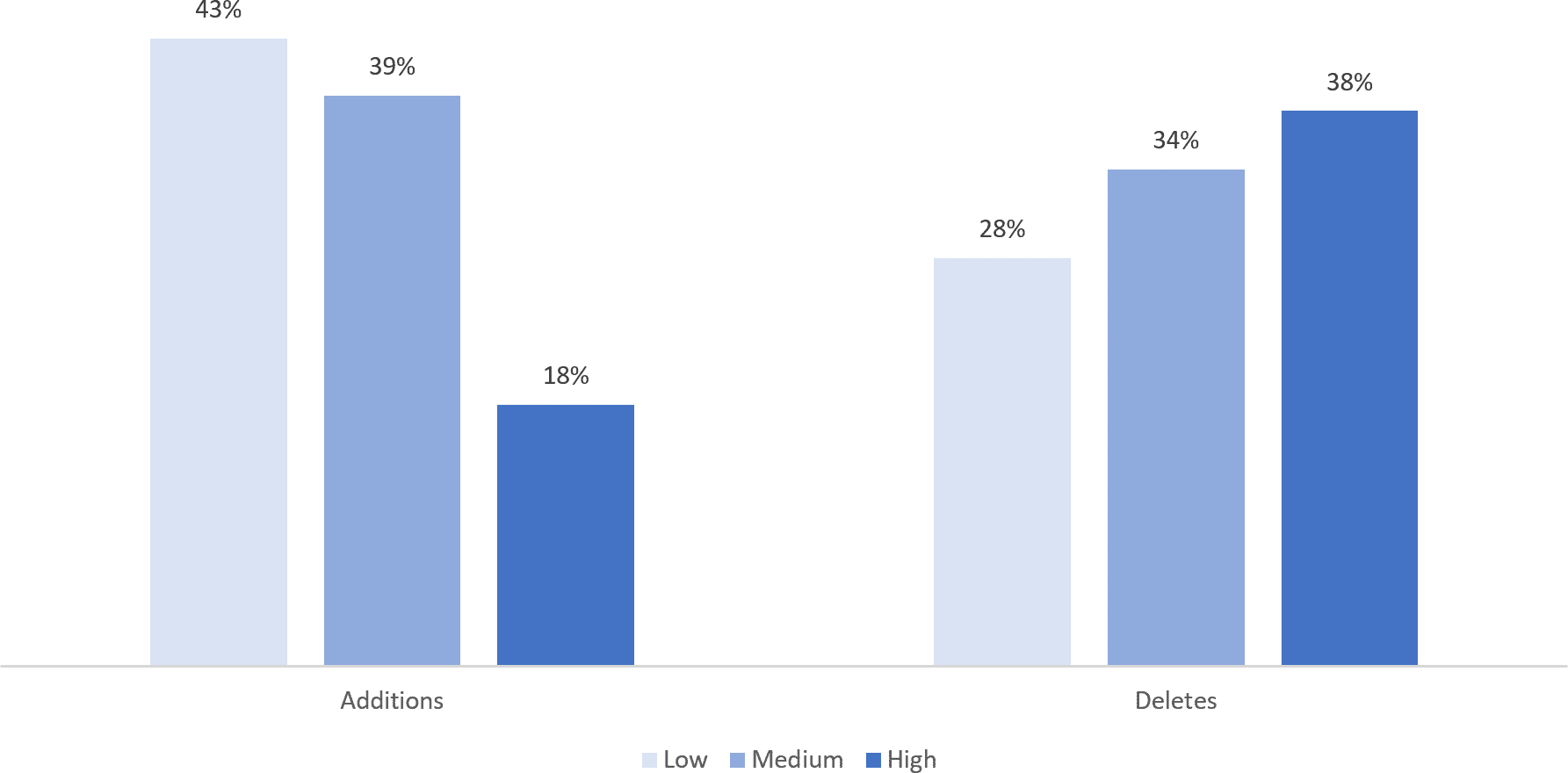

The chart below shows the distribution of supplemental diagnosis codes, both for additions and deletes, across the Low, Medium, and High failure rate groups. As described above, the frequency of HCCs is approximately equal across the 3 groups; however, that is not the case when just focusing on the HCCs identified through the supplemental diagnosis codes. Recall from the prior blog that these include codes which may have been missing from the original EDGE encounter submissions or for which there may have been an error. It appears that Low and Medium failure rate group HCCs are more likely to be added than High failure rate group HCCs. Since the three failure rate groups should be associated with a similar frequency, the distribution suggests HCCs in the High failure rate group may be more difficult for plans to track down in their medical record review efforts.

Exhibit: Proportion of Supplemental Diagnosis Codes that are in Low, Medium, and High Failure Rate Groups

Source: RaLytics, LLC analysis of the 2018 Enrollee-Level External Data Gathering Environment (EDGE) Limited Data Set (LDS).

Moreover, HCCs in the High failure rate group are more likely to show up as a deletion in the supplemental diagnoses code files. Again, this may be indicative of plans not being able to identify supporting medical record information for these types of conditions and consequently having to delete the diagnosis associated with the original EDGE submission. To the degree that this phenomenon does represent difficulties in medical documentation retrieval, it is particularly problematic for plans, especially considering that High failure rate HCCs are also associated with higher risk adjustment factors. The average risk adjustment factor for HCCs in the High failure rate group are over twice as high as those in the Low or Medium groups (9.6 compared to 4.7 and 4.7, respectively).

Thus, plans with a larger proportion of HCCs in the high-failure rate group may be at a disadvantage when it comes to the transfer payment, given their higher failure rate and larger risk factor. Reasons for difficulties validating these HCCs include challenges documenting conditions that are not being actively treated. For example, a clinician may be treating hemiplegia (muscle paralysis on one side of the body) that was caused by a stroke several months ago. In this case, the hemiplegia is the active condition that is being treated and can be validly documented. The stroke, even though it may be documented by the clinician, may be harder to validate based on just this visit, since it was a prior event. Another common example is when a chronic condition such as depression exists, but may not be appropriate to document when a patient comes in for something acute, such as a broken limb.

For these situations, other approaches that are not reliant on medical record documentation as the sole method for validation may be appropriate for plans in this situation. For example, there may be information on submitted EDGE encounters that point to medical and drug utilization indicative of a condition for payment validation purposes. In the case of the person with depression, rather than having to seek and review medical record documentation, encounters could be examined for a relevant history of relevant therapy visits or antidepressant drugs. Of course, such changes would require a regulatory overhaul of the ACA RADV process. In lieu of this, plans can also evaluate utilization data to identify which HCCs may be most at risk for deletes, or which could be added.